She saved the Alamo. Her hospital now saves lives — and her legacy

Clara Driscoll is one of the most important — and perhaps most overlooked — figures in Texas history.

Without her, the Alamo might not stand today. And without Driscoll Children’s Hospital, most of her story might not, either.

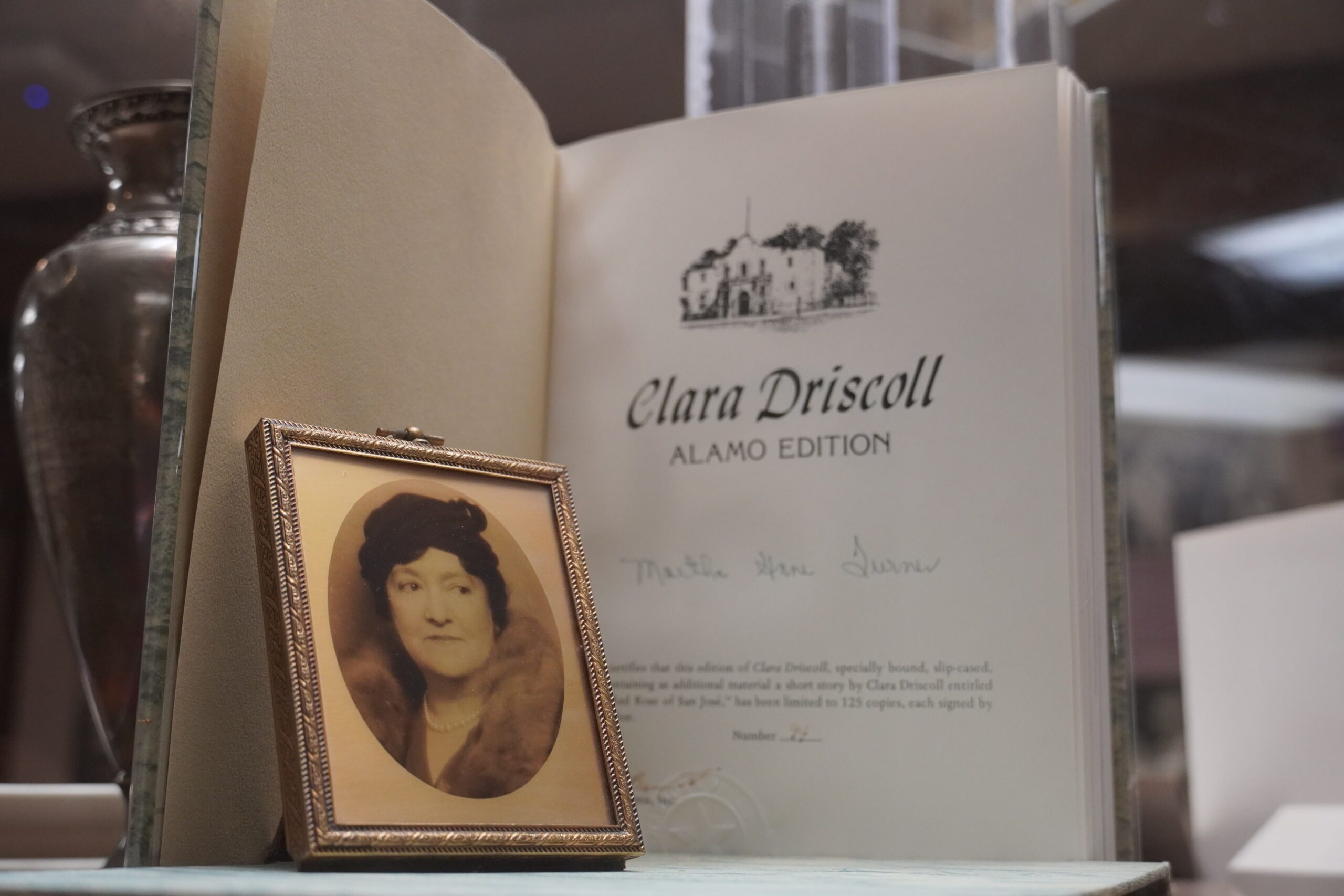

The hospital, which she helped create through a personal endowment, is now the unlikely home of the largest collection of Clara Driscoll’s records — more than any university or museum.

“She had kept all kinds of stuff, and nobody had touched it since maybe the ’50s,” said Carolyn Taylor, the hospital’s archivist.

Taylor found Clara’s papers sitting in a room gathering dust. One of the hospital’s first trustees had begun archiving the documents shortly after the hospital opened its doors in 1953, but he passed away before he could finish. For decades, the papers sat idle.

They could have been lost to time. But the hospital preserved them.

Driscoll Children’s Hospital may have started small, but today it plays a big role — not only in saving children’s lives, but in protecting Texas history.

‘Savior of the Alamo’

Clara Driscoll, the granddaughter of a Texas patriot, lived an extraordinary life. She was raised on her family’s Palo Alto Ranch about 20 miles west of Corpus Christi, attended boarding school in New York, lived in Paris and took a round-the-world trip with her mother and brother. But no matter where her adventures took her, Clara always came back to Texas.

When she learned that the Alamo was at risk of being torn down to make way for a hotel, she led an organizing effort to save the landmark.

With the clock ticking and money falling short, Clara gave $65,000 — the equivalent of more than $2.3 million today — to save the site.

“And then, years later, she helped again with another $65,000 to help buy some more land around the Alamo,” said Taylor.

The heroic act earned her the title “Savior of the Alamo.” But few today know her name.

That’s why Taylor’s work matters so much. The insights she has gleaned from countless hours in the time capsule of a room that holds Driscoll’s affairs show that the hospital is more than just a medical center — it’s the guardian of Clara’s legacy. And Taylor is its keeper.

“I love getting into all her history, putting everything in order, finding all the other documents,” Taylor explained, “and putting them where they belong.”

Preserving a legacy

It’s not the job Taylor thought she’d have back in 1997, when she began at the Driscoll Foundation as a receptionist. Over time, she worked her way up and felt more connected to the workplace she calls “very comfortable and loving.”

When a health issue forced her to leave behind her role in finances, she found her calling in the archives.

“It works a lot better for me, it's easier for me to handle all the archives, and I love it,” said Taylor.

She even hand-transcribes Clara’s letters one by one, deciphering her ornate cursive, so future generations can read them.

“I’m taking every document she’s ever written or had written to her, or whatever that’s in cursive, and I’m handwriting it out and putting it with the cursive document,” said Taylor, who is also cataloging Clara’s unpublished stories.

Taylor has also built a 130-page timeline on Clara Driscoll and the Alamo, along with one for Clara’s father, Robert Driscoll, Sr.; her mother, Julia Fox Driscoll; and brother, Robert Driscoll, Jr. Clara’s alone includes 75 lines — an impressive list of accomplishments and milestones that would stand out in any era: Elected National Democratic Committeewoman, president of Texas Picture Inc., president of Daughters of the Republic of Texas, owner and president of Corpus Christi Bank and Trust Company and even a “Special Deputy Sheriff” in Bexar County. She also wrote books and a three-act musical performed in four cities. She led. She gave.

Taylor is quick to point out that Clara’s gender and the era make her particularly noteworthy.

“You just didn’t do that back then, as a woman,” said Taylor. “But she did. And I think, ‘what would South Texas be like without her — and the Driscoll family?’”

Corpus Christi Naval Air Station, Del Mar College, Corpus Christi International Airport — all sit on land once tied to the Driscolls. Their legacy helped shape South Texas.

But unlike other Texas patriot families, the Driscoll family — and Clara’s story — was at risk of being forgotten, because her family line ended when she passed away in 1945.

“She was married and never had kids,” explained Taylor. “Her brother was never married, never had kids, so the line stops there.”

South Texas lifeline

That’s why the hospital matters so much. It’s not just Clara’s creation — it’s her legacy, still alive and growing.

Clara worked with her physician, Dr. McIver Furman, to donate money to start the hospital along with the foundation that still supports it: the Robert Driscoll and Julia Driscoll and Robert Driscoll Jr. Foundation. Today, it continues to serve thousands of children every year.

Driscoll Children’s Hospital cares for children and families all across South Texas — children who might not have access to expert medical care anywhere else — and it keeps expanding to meet growing needs, most recently in the Rio Grande Valley and increasingly beyond.

Taylor believes Clara would be proud.

Thanks to the fortune Clara Driscoll left behind, the hospital that began as a small 25-bed facility has grown into a regional leader in pediatric care, with expert specialists in more than 32 medical and 13 surgical specialties. Driscoll was the first hospital in South Texas to offer emergency services just for children — and today, it provides emergency care to around 40,000 young patients every year. It was also the first in South Texas to perform an organ transplant, continuing Clara’s legacy of bold firsts and lifesaving impact.

“She would be shocked at how big it’s grown,” said Taylor. “She would be so pleased and so thrilled that her money was able to do all this.”

Thanks to that gift, Driscoll Children’s Hospital does more than heal. It protects a story that shaped Texas — and might have vanished without it.